‘Everyone Wants to Build a Brain’

The demand for neuromorphic (brain-inspired) computer and software design has recently ballooned thanks to its combined low costs, low energy needs, and exceptional flexibility and computational power.

Since neuromorphic design is based on biological brains, its innovations cannot be built on classical computer architectures. Every layer of technology needs to be designed within the neuromorphic paradigm.

“To actually push something all the way to where we can use it to solve real-world problems, we need to have people working on new materials, new devices, new architectures, algorithms, and applications at the same time in an intentional, coordinated way,” said Katie Schuman, an assistant professor and algorithm expert in the Min H. Kao Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS).

With that goal in mind, Schuman initiated TENNLab, the University of Tennessee’s neuromorphic computing laboratory, in 2015. The founding faculty included Professor Emeritus Douglas Birdwell, an algorithm expert and Schuman’s former PhD advisor; Professor Jim Plank, the group’s software expert; and two hardware experts, Professor Emeritus Mark Dean and EECS Department Head Garrett Rose.

Over the last decade, TENNLab has partnered with the United States Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), Army Research Laboratory, Naval Research Laboratory, and Sandia National Laboratories; academic research partners at Purdue University, the University of Texas at San Antonio, and the Georgia Institute of Technology; and industry giants like Intel and Accenture.

“Our students have access to all the places neuromorphic computing is being researched,” said Plank. “Our group also gives them access to military projects, including work with cutting-edge companies like Areté and R-DEX, which students would have absolutely no ability to interact with otherwise.”

While some research groups in Europe conduct neuromorphic research across the compute stack, TENNLab is the only lab of its kind in the US.

“Right now, a lot of the student population in neuromorphic computing is European, but there’s a lot of interest from government organizations in the US,” Schuman said. “It’s critical that we train the workforce here to not just leverage the existing neuromorphic technologies, but also further their development.”

The Neuromorphic Experts

Neuromorphic computing is composed of simulated neurons (brain cells) and synapses (the spaces between neurons). The neurons and synapses are easier to construct than central processing units (CPUs) and other classical computer science architecture, making neuromorphic computing an appealing method to achieve inexpensive, low-power, robust computation.

“Most research entities—whether they’re small businesses or the military—reach a point where they realize they might need to integrate neuromorphic computing,” Plank said.

TENNLab’s first major break into the neuromorphic research space came after the group secured a grant in 2015 from the AFRL. The resulting publications led to several additional rounds of AFRL research funding—totaling more than $5 million by 2026—and the attention of many more government, industry, and academic partners.

“Now, when people want to look into neuromorphic computing for their projects, they know they should come to us,” said Plank.

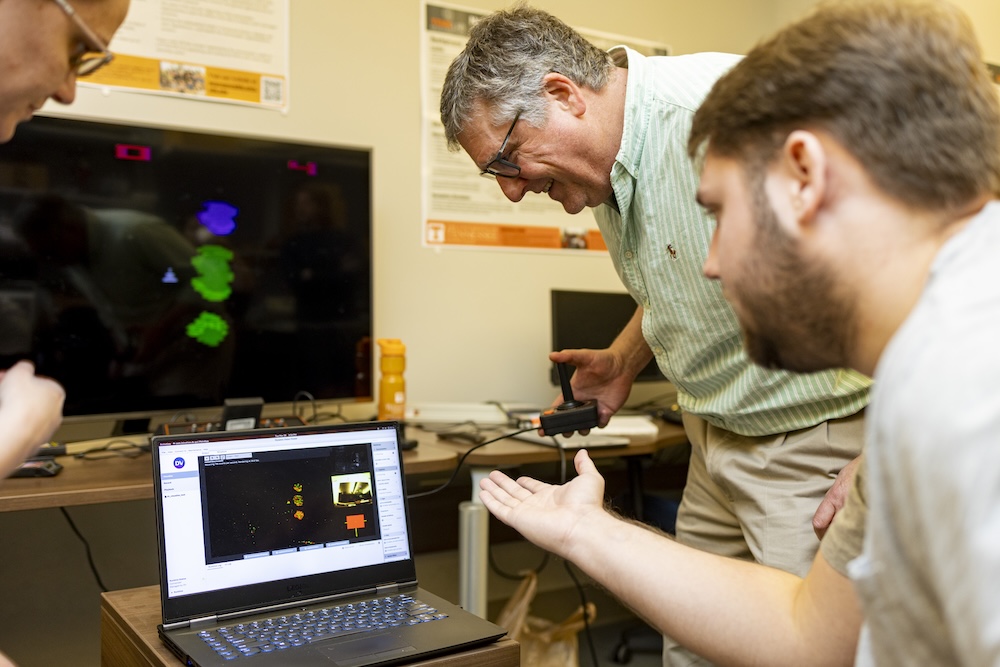

Collaboration and Workforce Preparedness

TENNLab builds great neuromorphic products by integrating every level of technological development and builds great neuromorphic workforce the same way—with a team that includes researchers from the undergraduate level on upward.

“Everyone wants to build a brain, and our students have a unique advantage in that they get firsthand experience on the entire spectrum of neuromorphic computing,” Plank said. “Whenever an undergrad expresses interest, we say, ‘Come to our meetings. And if you want to work with us, start working with us.’”

While graduate students are focused on narrower research topics, undergraduates are eager to explore the full neuromorphic space. TENNLab faculty encourage undergrads to effectively rotate through the compute stack, receiving guidance in various specialties from graduate students who in turn gain experience mentoring young scientists.

Meanwhile, students at all levels are constantly collaborating with researchers in government and industry labs or at other academic institutions.

“Our students are not just talking to other computer scientists and computer engineers; they’re working with electrical engineers, materials scientists, and physicists,” Schuman said. “They’re learning how to do cross-disciplinary research effectively, which is critical not only to neuromorphic computing but to science in general.”

Indeed, TENNLab alumni have gone on to positions across the computational field—from government research agencies like Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the National Institute of Standards and Technology to industry startups like Neural Magic and even titans like Google and Texas Instruments.

Many of them continue collaborating with the TENNLab team long after graduation.

“When we continue our interdisciplinary work and communication with these alumni who are building up their own teams and students, we are helping construct a common neuromorphic language,” Schuman said. “This is a foundation of collaboration that will be passed on to the next generation of neuromorphic computing experts.”

Contact

Izzie Gall (egall4@utk.edu)